Defense Research

Explanation of source links: Throughout the research below, you will find links of three types. The first and most frequent type is to primary sources such as governmental agencies. The second is to nonprofit groups that generally use government data or their own research to support their philanthropic mission. We have tried to use the least biased of these, or when in doubt, we have identified their bias. The third is to articles in periodicals or newspapers that we find to be of interest. These are not meant to be construed as original sources, and in some cases may not be accessible, depending on a reader's frequency of prior visits to the linked periodical or newspaper.

How much does the US spend on defense?

As of June 2025, the Pentagon was requesting $961.6 billion for its “base” budget in fiscal year 2026. Not to be confused with funding for military bases, the “base” budget is the recurring annual budget for the Department of Defense (DoD). These are the military’s primary, predictable expenses. Certain components of this budget were amplified to the tune of $150 billion in the 2026 reconciliation bill.

Reconciliation expenses added to the “base” budget are discretionary, reflecting the priorities of Congress and the President.

When related expenditures in other departments are included, such as overseas contingency funding, veterans’ benefits and services ($450 billion in 2026), and the cost of the nuclear arsenal (roughly $40 billion), total defense spending rises to over $1.4 trillion.

What are the major components of this spending?

Major components of the $961 billion:

Procurement: $205 billion – (this covers new weapons systems, vehicles, aircraft, ships, and equipment)

Military Personnel: $184 billion – (salaries, benefits, and personnel costs)

Operations and Maintenance: $107 billion – (day-to-day operations, training, facility maintenance)

Military Construction: $19.8 billion – (infrastructure and facility construction)

Research and Development: $1.2 billion – (new technology development and testing)

By service branch:

Air Force and Space Force: $301.1 billion

Navy: $292.2 billion – (including Marine Corps)

Army: $197.4 billion

Defense-Wide Activities: $170.9 billion – (special operations, intelligence agencies, and other joint activities)

HOW MANY PEOPLE DOES THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE EMPLOY?

In 2025, the US had only 1.3 million active-duty soldiers, the smallest force since WW2. In addition, the National Guard/Reserves number 760,000 and the military employs 790,000 civilians, for a grand total of 2.86 million. The following chart from USA FACTS shows how this number has remained relatively stable since winding down after the Vietnam War. Note: chart excludes the Coast Guard.

SEE ALSO:

How has this spending fluctuated over time?

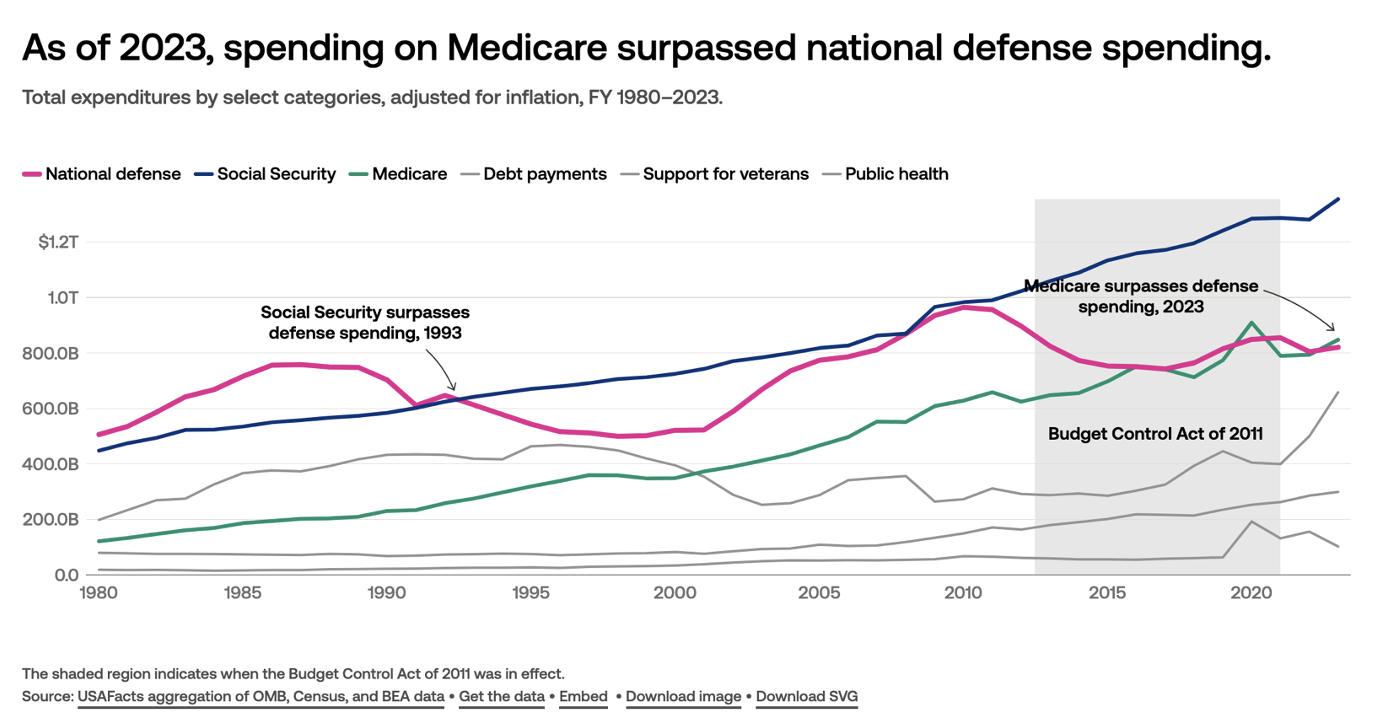

Measured in 2011 dollars, real spending declined from $550 billion in 1988 to $375 billion in 1999, before increasing again. This savings was referred to as the “peace dividend” in reference to the de-escalation of US-Soviet tensions.

Source: https://usafacts.org/articles/how-much-does-the-us-spend-on-the-military/

How does this compare to the spending of other countries?

According to the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, the US spent more in 2023 on defense than China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, India, France, the UK, and Japan combined:

Further, the US spends a higher percentage of its total federal budget on defense (13.3%) than any other large industrialized country. This is also true when measured in terms of GDP:

In comparison, China spends around 1.4% of its GDP on defense. France, the UK, and Germany also spend less than 3%, with Germany at about 2.1%, France at 2.1%, and the UK at 2.3%.

WHY DOES THE US SPEND SO MUCH MORE THAN OTHER COUNTRIES?

One reason is that, unlike other countries, the US has a national security and national defense strategy based on global military dominance. To support this goal, the US has 800 bases in 80 countries. No other country has this kind of presence, as indicated below. The infrastructure alone costs approximately $80 billion per year or over $100 billion when counting domestic bases. The following chart identifies the global locations of active duty troops stationed at overseas bases.

IN WHAT WAYS IS THE US’S MILITARY APPROACH UNIQUE?

Global Presence:

No other country has a comparable global presence. The US maintains approximately 750 military installations globally. The UK comes in second with 140, while Russia has two, and China has only six. However, these numbers fluctuate depending on how one defines “military base”; in the strictest possible sense (permanent military personnel, located outside the country, under direct control as opposed to an access agreement, combat-ready infrastructure), the US has 90 and the UK has 20.

Perpetual War

US defense spending has funded a perpetual state of war around the globe. In total, the US military is estimated to have been deployed 250 times between 1948 and 2025. Many of these were peacekeeping missions at the invitation of existing governments; others were to assist in the peaceful evacuation of Americans abroad or in the defense of our embassies. There have also been actions in response to perceived aggression by other countries in their sphere of influence. For example, the US conducted military exercises in the Middle East that subsequently drew fire from Libya and Iran. Each of these incidents was then followed by a military response. Arguably, these incidents could have been avoided had we not been in the region in the first place.

Unprovoked Intervention

Even after removing all of the above incidents from the total, we are still left with 50 wars of choice since WWII, unrelated to our own defense, making the US the most warlike nation on the planet. Many of these were actions throughout Latin America conducted in cooperation with the CIA to effect regime change.

The following is a list of post-WW2 US military engagements, divided into five subgroups: full-scale wars, CIA regime change, military intervention (small wars), counterterrorism, and proxy support.

Full-Scale Wars & Major Combat Operations

These involved large-scale deployments and sustained combat operations, often under formal declarations of war or authorizations for use of military force:

1950–1953: Korean War

1955–1975: Vietnam War

1991: Iraq (Desert Storm)

2001–2021: Afghanistan

2003–2011: Iraq War

2014–present: Syria (anti-ISIS operations)

CIA-Backed Regime Change & Covert Interventions

Primarily intelligence-led operations, often involving coups, assassinations, or proxy support with little public acknowledgment:

1953: Iran

1953: Guyana

1961: Bay of Pigs

1963: Guatemala

1963: Honduras

1964: Bolivia

1964: Brazil

1970: Cambodia

1971: Bolivia

1973: Chile

1979–1980: El Salvador

1979: Nicaragua

1982–1983: Guatemala

1988–1989: Chile

1989: Philippines

Military Interventions & Occupations ("Small Wars")

Short- to medium-term operations with US troop deployments or airstrikes, typically not involving long-term occupations:

1949: Panama

1958: Lebanon

1961: Dominican Republic

1965: Dominican Republic

1969: Panama

1983: Grenada

1986: Libya

1988–1989: Panama

1993: Somalia

1994: Haiti

1995: Bosnia

1996: Kuwait

1999: Serbia

1999: East Timor

2011: Libya

2017: The Philippines

Ongoing or Decentralized Counterterrorism Operations

Primarily post-9/11 efforts involving drone strikes, special operations, and surveillance, with minimal ground presence:

1998: Afghanistan and Sudan

2002: Yemen

2004–present: Drone strikes and counterterrorism operations in Pakistan, Kenya, Ethiopia, Yemen, Eritrea, Georgia, Somalia

2014: Somalia

2014: Niger

2015: Yemen

Security Assistance / Proxy Support / Counterinsurgency Aid

US involvement through training, arms transfers, funding, or intelligence to allied or proxy forces, often in civil conflicts:

1961: El Salvador

1962–1974: Laos

1968: Laos and Cambodia

1983: Honduras

2002–2010s: Georgia

DOES THE MILITARY ITSELF THINK ALL OF THIS SPENDING IS NECESSARY?

No; there have been many cases of Congress requiring the military to fund projects that are important to individual representatives and senators, but are not important to the military. For example, members of congress and governors have frequently objected to the military’s efforts to close antiquated US bases and reduce the size of its civilian workforce.

To provide some order to the management of Dod base closure recommendations, Congress passed the Defense Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Act of 1990. The act created a commission that would receive and review the recommendations before their submission to Congress.

In 2017, the acting assistant secretary of defense provided the following testimony on the subject of BRAC: “The Department urges Congress to authorize one new round of base closures and realignments, in 2021, using the statutory commission process that has proven, repeatedly, to be the only effective and fair way to eliminate excess DoD infrastructure and to reconfigure what must remain.”

The last formal BRAC round that resulted in closures occurred in 2005. Although there were discussions and internal reviews afterward, no official BRAC round has taken place since then, and the most recent BRAC-related proposals (in 2015 and later) did not result in base closures due to lack of congressional authorization. BRAC rounds are not conducted on a fixed schedule—they require congressional approval, and the DoD has repeatedly requested new BRAC rounds in budget submissions since 2013, but none has been approved.

Over the past two decades, the DoD has experienced major shifts in force structure, global posture, mission priorities, and emerging threats, particularly with the strategic pivot toward competition with China and Russia.

Additionally, while the Budget Control Act of 2011 expired in 2021, its long-term effects on defense planning and infrastructure investment persist. As of 2025, the DoD continues to face resource constraints and admits it cannot fully fund all sustainment requirements for its aging infrastructure portfolio. The limited construction and maintenance funding is better used in locations with the highest military value rather than installations the DoD does not need. “About 20% of the Pentagon's facilities could be closed without negative impact,” - John Roth, the acting budget chief in 2022.

RUSSIA AND CHINA ARE GENERALLY CONSIDERED THE US’S PRIMARY COMPETITORS GEOPOLITICALLY AND MILITARILY. WHAT ARE THE HISTORICAL CONTEXTS FOR THESE RIVALRIES, AND WHERE DO THEY STAND TODAY?

RUSSIA:

Since the Soviet Union's dissolution in 1991, NATO has expanded to include former Soviet or Warsaw Pact states like the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland (1999), Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia (2004), Albania, Croatia (2009), and Montenegro (2017), bringing NATO’s borders closer to Russia, which shares a 1,215-mile border with Norway and maritime boundaries in the Baltic and Black Seas.

Russia’s 2024 defense spending was approximately $61.5 billion, or 3.5% of the $1.75 trillion combined budgets of the US and its allies. As previously noted, the US operates around 800 overseas bases, while Russia maintains nine, mostly in former Soviet states and Syria.

Since World War II, Russia has engaged in conflicts in Afghanistan (1979–1989), Georgia (2008), Ukraine (2014, 2022–present), and Syria (2015–present, at Syria’s invitation).

In 2014, Russia invaded and annexed Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula, a stretch of territory with strategically access to the Black Sea. In 2022, it began a full-scale invasion of Ukraine that has since settled into an ongoing war of attrition as of 2025, with marginal territorial gains and over a million total deaths. These invasions followed 2008 discussions about Ukraine’s potential NATO membership. Ukraine, shares a 1,426-mile border with Russia and hosts ethnic Russians and Russia’s Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol, a key naval base for Mediterranean access. Russia’s strategic interests focus on securing its borders and trade routes, particularly in the Black Sea and Baltic Sea.

The US has supported Ukraine with over $75 billion in military aid since 2022, providing weapons, intelligence, and training without direct troop involvement. President Biden took a firm stance in favor of aid to Ukraine throughout his term. President Trump has expressed skepticism about sustained US support for Ukraine and NATO’s role, advocating for reduced commitments and favoring sanctions, collaboration with NATO, and direct negotiation with President Putin.

Territorial standing of the Russo-Ukrainian war as of 2025. Russian occupied territory in orange.

Source: Al Jazeera

CHINA:

China has been involved in about 13 conflicts since World War II, mostly border disputes like the Korean War (1950–1953), Sino-Indian War (1962), and Vietnam clashes (1979). Its 2024 defense spending was officially $232 billion, though adjusted estimates suggest $474 billion, about 36% of the US’s $1.3 trillion.

In the South China Sea, China has militarized artificial islands to control disputed territories critical for $3.4 trillion in annual maritime trade, including 40% of its own trade. The US maintains a naval presence there to ensure freedom of navigation. Through the Belt and Road Initiative, launched in 2013, China has invested over $1 trillion in global infrastructure, enhancing trade routes and economic ties in Asia, Africa, Europe, and Latin America.

As the US’s largest trading partner, with $575 billion in 2024 bilateral trade, China holds $749 billion in US debt, up from $105.6 billion in 2000.

China’s priorities include securing South China Sea trade routes, expanding economic influence, and maintaining border stability.

US-China tensions have escalated over Taiwan, with the US increasing arms sales and naval transits through the Taiwan Strait, while China conducts frequent military exercises simulating blockades. Taiwan produces over 60% of the world’s semiconductors, which are critical for technology and defense; control over these supply chains impacts global economic and military power.

WHAT IS THE LEVEL OF GLOBAL SPENDING BY THE US AND OUR ALLIES?

Comparisons of defense spending by country only tell part of the story. It is also important to consider how much our allies spend compared to Russia or China individually. In 2024, NATO members spent approximately $1.45 trillion on defense, the highest amount ever recorded by the alliance. This was 19 times Russia’s estimated spending and six to seven times China’s. In 2023, 11 of the 32 members met the NATO target of spending at least 2% of GDP on defense; 23 members were expected to meet the target in 2024.

WHAT ARE THE BASIC ELEMENTS OF THE DEBATE ABOUT DEFENSE SPENDING?

There is a lot of scholarship about the US military complex being obsolete in the modern world. Some cite the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq (and sometimes even as far back as Vietnam) as evidence that “the best trained, best equipped, most modern military in the world” is incapable of stopping terrorists and other threats to national security. They argue that the US is preparing for a massive land war that may never again happen. The US spends more on its military than every other nation in the world, but has been ineffective in pacifying small, impoverished nations.

While this is an academic perspective of current military spending, it seems to be relevant to the general populace. Time reported in 2016 that “A majority of voters surveyed between December 2015 and February 2016 … said they wanted defense cuts in almost every area of the military.”

Despite this widespread mentality, most politicians (Democratic and Republican) publicly oppose military budget cuts.

For our specific defense policy recommendation, please click here.