Richard Nixon, President Trump, and the Price of Oil

(545 words, two-minute read)

Richard Nixon famously said to David Frost, “Well, when the president does it…that means that it is not illegal.” We all know how that ended. President Trump recently engaged in negotiations to increase the price of oil. Although it might not have helped much, price fixing in the US is illegal. What are we to make of this? Was there a better, and legal, policy response?

I think the answer is yes, and it lies in distinguishing between two unrelated events, both occurring in February, and both contributing to the abrupt decline of oil prices that followed.

Two things shocked the oil market

Event One: In a competition for market share, both Russia and Saudi Arabia (both in the top five of producers and entirely oil dependent) began expanding production.

Event Two: At roughly the same time, demand for oil began to decline precipitously as the global economy contracted due to the COVID crisis.

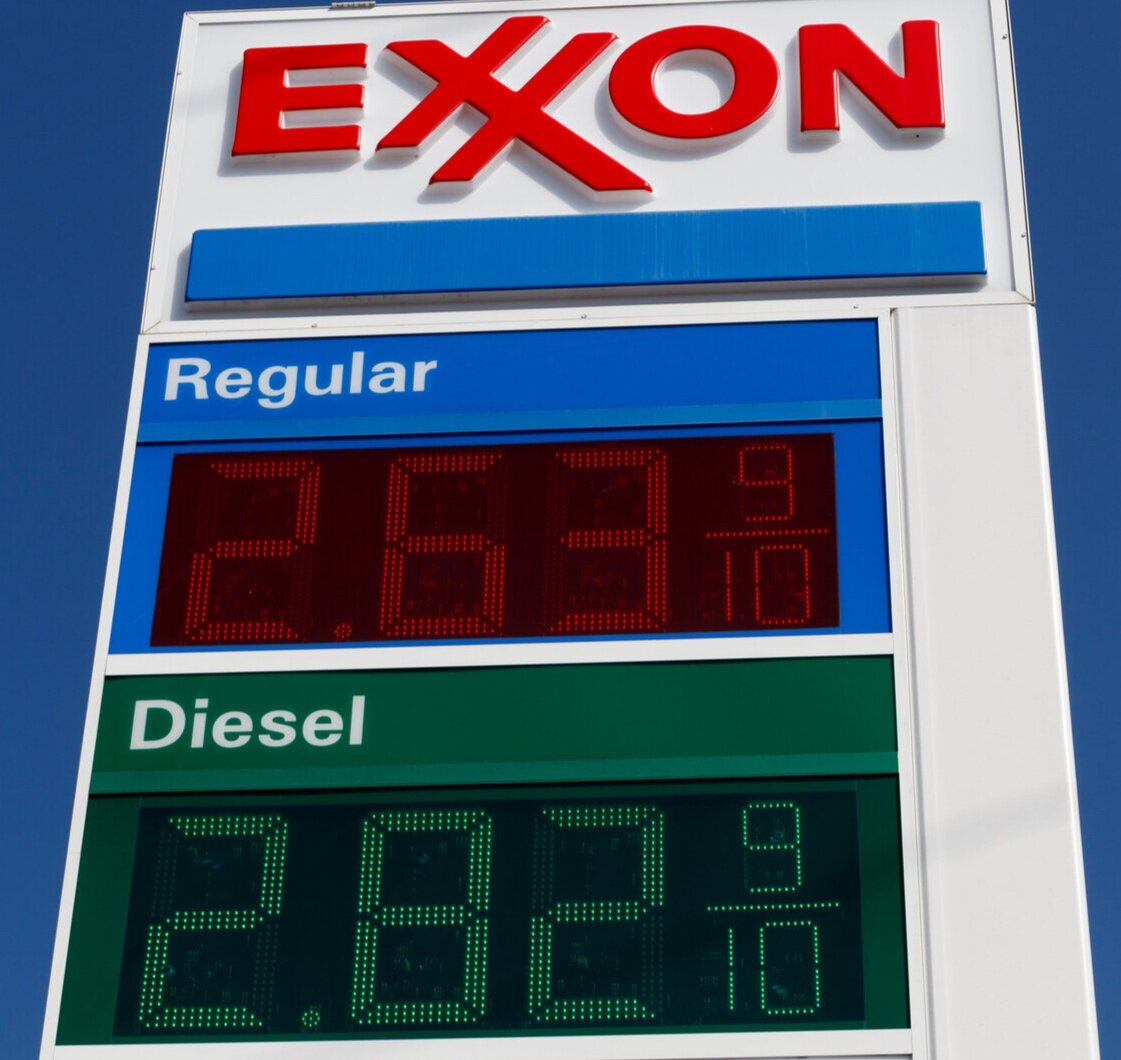

These two events combined to drive the price of oil from over $50 per barrel to under $20. Trump initially applauded the falling price and announced that he would take advantage of it by adding to the nation’s strategic oil reserve.

Who won, who lost?

The price decline has created winners and losers. The losers are easy to identify and can marshal political influence in order to control their losses. This would be the oil-producing countries, companies, drillers, pipelines, etc.

The winners are everyone else, meaning that every consumer and every manufacturer on the planet is now paying less for their energy. This is the equivalent of a massive tax cut or stimulus package, and the global economy benefits enormously. At a time when the global economy is suffering, a lower price of oil is particularly beneficial.

The losers get a rescue

Despite this benefit, the oil lobby persuaded the president that the benefits to everyone were not worth the potential loss of earnings and jobs within their industry. Since there is no lobby to represent the public at large, there was no one to argue the other side. This is the essence of how special interests prevail.

In order to try to raise prices, the president played a role in negotiating production cuts, principally by Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Mexico. Such collusion in any other industry would clearly violate market regulations and would not be allowed. Section One of the Sherman Antitrust Act identifies price fixing as a criminal federal offense. Exchanging prices among competitors can also violate the antitrust laws. Rather than objecting, many in the media applauded.

So, what could he have done better?

Response to Event One: None. To the degree that the price decline was related to the Russian and Saudi Arabian competition for market share, no response was justified. In normal times, the price of oil fluctuates, countries and companies battle for share, and the industry should be left to fend for itself.

Response to Event Two: Use the CARES Act. Much of the decline, however, was the result of the world’s policy response to the COVID crisis. In this case, there has been a bipartisan consensus that many companies hurt by the crisis should receive some government assistance, hence the passage of the $2.2 trillion CARES Act. If it is deemed necessary, the simple and most transparent way to help the industry would be for them to be eligible for CARES assistance on the same basis as are other industries.

By using the CARES program, taxpayers can let the market work while still assisting the companies that they deem strategic. The cost involved as well as the benefit will be simple to measure. To do otherwise is not only legally questionable, but it taxes all consumers indiscriminatingly in order to benefit a particular industry.