The Cost of Universal Healthcare

Opponents of universal healthcare seized on a recent estimate by the Mercatus Center that Bernie Sanders’s Medicare for All proposal would cost the federal government at least $32 trillion over the next 10 years. Their view is that this estimate provides self-evident proof that it is unaffordable and, therefore, not worth discussing. Is it a sensible argument? The answer to that is not so clear. Let’s try to be fact-based and rational.

First, is the estimate reasonable? While Sanders doesn’t think so (and charges that the Koch-brothers-supported Mercatus Center is biased), there are other credible estimates available in the same range. Today, as is discussed in our Healthcare Research, total spending on healthcare in the US is 18% of US GDP. This includes the amount the government spends (Medicare, Medicaid, etc.) and what individuals and their employers spend pursuant to private health insurance (premiums, deductibles, copays, etc.). GDP was $20.5 trillion in 2018, so at 18% spending on healthcare would have been approximately $3.7 trillion. Multiple this by 10 years, and even without inflation you have $37 trillion. So simple math would suggest that the Mercatus estimate is within the ballpark.

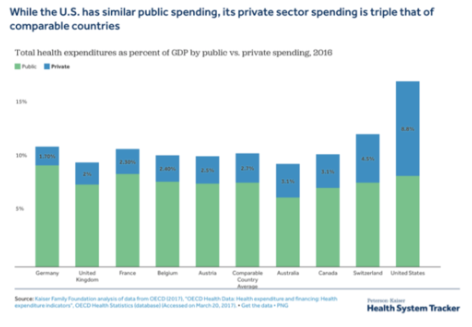

Given that, while there are many issues to debate regarding the prospect of universal healthcare, does it follow that cost alone means it is not worth discussing? Like most things, it depends. Here is another way to look at this issue. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, government spending on healthcare in the US is 47% of the total, meaning 8.5% of GDP. This is roughly equal to government spending (as a percentage of GDP) in Germany, the UK, France, Belgium, Austria, Canada, and Switzerland. The difference is that government spending in each of these countries enables a baseline of coverage for all citizens. In effect, the private sector in the US makes up for the amount by which US total healthcare spending exceeds that of comparable countries.

How can this be? The answer lies in the part of the discussion that is frequently left out of the public debate. All successful universal plans control cost by doing three things: 1: they eliminate for-profit insurers as the administrators of healthcare; 2: they control drug prices, thereby paying as little as ⅓ of what Americans pay; and 3: they control what they pay medical providers. By doing so, they actually provide more healthcare, not less (as an example, according to the Commonwealth Fund, the average person in France, Germany and Japan sees a doctor six to eight times per year, while the average American sees one three to four times per year), and achieve outcomes by several conventional measures that are better.

What is the conclusion? Done right, it seems reasonable for Americans to aspire to having a healthcare system with better outcomes that costs the federal government no more than it currently spends.